- Home

- Marcia Strykowski

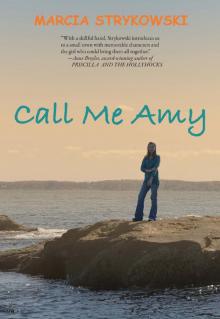

Call Me Amy

Call Me Amy Read online

CALL ME AMY

MARCIA STRYKOWSKI

LUMINIS BOOKS

Published by Luminis Books

1950 East Greyhound Pass, #18, PMB 280,

Carmel, Indiana, 46033, U.S.A.

Copyright © Marcia Strykowski, 2013

PUBLISHER’S NOTICE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover Photo & Author Photo by Thompson Photography & Graphic Design. Cover design by Joanne Riske.

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-935462-76-7

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-935462-75-0

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my parents,

Raymond and Margaret Sorensen,

with love and gratitude.

Early praise for Call Me Amy:

“A wounded seal pup propels 13-year-old Amy Henderson into an unlikely alliance with an unusual older woman and a mysterious boy in a small Maine fishing village. Readers will cheer for Amy as she protects Pup, gains confidence, faces challenges, and comes up with an idea that could change not only the future of her village, but also her own life. With a skillful hand, Strykowski introduces us to a small town with memorable characters and the girl who could bring them all together.”

—Anne Broyles, award-winning author of Priscilla and the Hollyhocks

“In a small town in Maine in the 1970’s, Amy is standing on the brink of becoming a young adult. The events that will force her to discover who she is, what she is made of and how she wants others to perceive her are sweetly told through awkward teenage moments, the triumphs and sadnesses of that age and, ultimately, Amy’s discovery of her own beliefs, strength and courage.”

—Kathleen Benner Duble, acclaimed author of The Sacrifice

“Well-drawn, sympathetic characters and the developing spark between Amy and Craig combine to create a pleasant, satisfying read.”

—Kirkus

“Strykowski ably depicts Amy’s insecurity and self-doubt, Craig’s bravura and pain, and Miss Cogshell’s wisdom with a deft, convincing touch. In essence, Amy comes of age as she fights to find her voice in the outside world and shed some of her debilitating insecurity. Readers will cheer her on, and her splendid team too.”

—Booklist

Acknowledgments

Along with Mom and Dad, thank you to Bette, Bob, Derek, and Marla for your ongoing love and support. And special thanks to all the writers and readers who read Call Me Amy in its various stages. Also, thank you to Tracy Richardson and Chris Katsaropoulos of Luminis Books.

CALL ME AMY

1

SHARP OCEAN AIR raced around my bedroom before I slammed the windows shut and headed downstairs.

My big sister Nancy called out to me. “Are you going for a walk by yourself again?” She swung her dark, glossy ponytail over one straight shoulder.

I nodded as I stooped to pull on my boots.

Nancy, as different from me as perfume is to tiddlywinks, was sprawled across the kitchen linoleum. Seventeen magazine lay open while Carly Simon’s hit song “You’re So Vain” blared from her transistor radio. Nancy had little wads of cotton stuffed between her toes, so her shiny, pink toenails wouldn’t smudge. I blocked my nose, hoping to get out of there fast before the smell of nail polish made me puke.

“You know, Amy, you really should try to make some friends—so you don’t have to mope around by yourself every Saturday. There must be somebody else your age in this boring port.”

Duh. What was I supposed to say to that?

“I’m telling you,” continued Nancy, raising her voice over the music as she examined her toes, “just two more years and I’ll kiss this hole-in-the-wall town goodbye.”

I slipped into my yellow parka and pushed open the door, ignoring her. The breeze swept in to flip the pages of Nancy’s magazine.

“Check the post office for me!” Nancy’s shout came faint against the wind just before the door blew shut.

I was already halfway down the hill, and most likely I would end up at the post office. Where else would I go? In Port Wells there were only so many places to visit, so the pier, Al’s General Store, and the post office were at the top of the list. For the religious sort, there was a Baptist church across from the post office. Its steeple was the first thing you’d spot when coming around the corner off the main road.

Oh, and how could I forget—for those who liked smelly little bait shops, there was one of those, sticking off the back of the general store. A simple thing like wanting to buy a pair of bellbottoms or borrow a library book meant going into Thomaston—thirty miles away. The sparkle of the salt air and surf made living on the coast all worth it, though.

I slowed my pace and took tiny steps down the hill through the pine trees, my boots flattening the last of the snow. As much as I hated to admit it, I knew Nancy was right. So far, 1973 had been a lonely year.

My best, or I guess you could say only friend moved away last spring and had turned out to be a lousy letter writer. Like, none at all. I had spent half the summer hanging around the post office waiting for a letter, postcard, anything, until I finally gave up sending my own weekly letters.

Now, after being stuck inside most of the winter, people were poking their heads out. Port Wells was slowly coming alive again. A couple of townies were home safe from Vietnam and folks seemed more relaxed. There was a hint of spring in the air. Just a hint—for in Maine, spring was sluggish. Colors were as vivid as a new tin of watercolor paints: viridian green trees against cobalt blue with zinc white clouds. I could hear the Percy boys shrieking out baseball calls from the village field.

I looked back up the hill, through the pines, at our Victorian-style house and inhaled the damp, salt air. Years ago my great-grandparents had come to Port Wells to build up their health. They used to say if they could only bottle this fresh atmosphere and sell it as medicine, then they’d be millionaires. They swore by it, and us Hendersons had been here ever since.

Down at the base of our hill I found an open area that was almost green and bare of snow. I flipped a cartwheel. The coarse ground left tiny pebble dents in my palms. I rubbed them together and flipped again, the rush of freedom outweighing any pain.

Then I heard a few dull claps. I spun around, peeked through my tangled hair, and found Craig Miller sitting halfway up a tree applauding me. Great. I couldn’t see all of him, mostly just his old army jacket. He wore it every single day.

“Encore, Shrimp, encore.” Ugh, I hated that nick-name. Craig scrunched down to peer through the branches at me. My face felt hot. I glanced at an imaginary watch on my wrist, as though late for some important event. The last thing I wanted to see was his foolish grin.

Craig was one of those tough kids whom all the boy-crazy girls giggled about, although he never seemed to notice. Too cool, I guess. He’d been in my class since first grade and even though we were in eighth grade now, I still didn’t feel comfortable with him. I usually ended up in the desk beside him because teachers thought it clever to put a silent student, like me, next to a big mouth like him. It’s not like I chose to be silent; I just never had anything to say that someone wasn’t already saying.

Craig had no problem spitting out whatever came into his head and it was sometimes hard to tell if he was joking or not. He was only one of the kids who called me Shrimp on a regular basis. I’m not sure when or why it started. I mean, I knew I was small for my age, but did that give everybody the right to compare me to a slimy piece of seafood?

I heard a low chuckle from the tre

e and took off, glancing over one shoulder to make sure I wasn’t being followed—fat chance—as I raced across the field between baseball innings. The players, all three of them, were taking a break. When I reached the pier I slowed down to catch my breath.

I could make out Wàwàckèchi Island sharp in the distance, and could almost see the lighthouse, a vague shape jutting upwards. Most mornings the fog came in so thick, you wouldn’t even know an island was out there. There was never a time I could pass by the ocean without stopping to stare, and, for all its blemishes, I truly believed Port Wells to be the most beautiful place on earth.

Today the water was calm with a few dinghies drifting on the horizon. The mail boat, surrounded by chunks of ice, waited by the pier. Soon it would make its daily trip out to Wàwàckèchi. On the other side of the wharf, an old fisherman in slippery yellow coveralls was squatting down by a bucket of red paint that would bring stripes to a long row of lobster buoys. I watched a minute, and then moved on.

Even Old Coot’s house didn’t look quite so drab on a day like this. But I still stayed way over on the opposite side of the lane—just in case.

Before I got to the post office, I stopped to watch three girls a little bit younger than me who were hanging around the gas pump outside Al’s General Store. Out of the corner of my eye I could see them gesturing and pulling at each other, talking and laughing like there was no tomorrow. I wondered what in the world they could be talking about. What did anyone talk about besides homework assignments or the weather? They were probably too young to be discussing Nixon’s Watergate problems. Would these girls clam up like I did, around the time they got their first zit? Probably not. Might as well face it, I was doomed to be an outcast forever. I found a smooth white pebble and kicked it along until it bounced off the wooden steps of the post office.

As I pushed open the post office door, smells of musty paper lunged from the darkened corners. Sally Johnson, the most chipper postmistress in the world, greeted me.

“Well, hello there, Miss Nancy. How is everything up on your hill?”

“I’m Amy.”

“What’s that?”

“Amy,” I whispered. Since I’d been going to school with her snotty daughter, Pamela, for all of my life, you’d think she’d at least know my name by now. I shifted my weight and fiddled with my parka’s zipper pull.

“Well, yes, let’s see. I think we have some mail here for your family.” She paused, stuck one finger in her ear, and glanced around at the small stacks of mail. “Ah, here it is,” she announced as she examined her finger for wax. I looked away disgusted, and wondered why there couldn’t be a more pleasant place to visit. Everyone knew that Sally listened in on telephone party lines and for all we knew she probably read the mail too, sealing it up again with her earwax. Yuck. I shivered, then realized she was talking to me.

“ . . . hasn’t picked up her mail lately and it’s piling up. You’ll be going right by Miss Cogshell’s place.” Sally peered at the envelopes as if deciding whether she approved of their contents. “I’ll put all this in a rubber band and you can bring it over there.”

My mouth fell open. Miss Cogshell was Old Coot! The most terrifying person in Port Wells and I was supposed to casually drop in on her? “But . . . ”

Sally had already turned her back and didn’t hear my timid protest. With clammy hands I took the extra bundle and headed out the door.

2

GOING TO OLD Coot’s house had even less appeal than painting my toenails. I could recall bits and pieces of gossip about the old lady who lived at the end of the road. She was the largest, scariest, most ugly woman we kids had ever seen. From the safety of the school bus windows, the kids all said she was a witch and called her Old Coot. I never called her anything, out loud. I always sat at the front of the bus, second seat on the right, staring straight ahead for the whole long ride—halfway to Thomaston. Old Coot didn’t venture out much, except for short walks back and forth to the general store. She used an odd-looking cane on those excursions.

I decided my best bet would be to leave her mail by the door and run. I glanced at my own pile. One was addressed to Nancy in scribbled handwriting. I rolled my eyes. Must be that gross boy she met last summer at camp. I held the envelope up towards where the sun had been, hoping to read it, but no luck. “Amy,” I could picture Nancy’s voice saying, “you’re getting as nosy as Postmistress Sally.”

There were several bills and letters for my parents. Without meaning to, I began peeking through Miss Cogshell’s large bundle of mail. Exotic stamps were on several of them—France, England, Africa. Who would write to her?

Soon I found myself in front of the small house by the pier. The sun had slipped behind the clouds, and turned the sea a dull grey. Miss Cogshell’s place, weathered from ocean winds, always appeared dark and dreary. A tiny, enclosed widow’s walk stuck out from the top of her roof. Its only window overlooked the harbor. I pulled my eyes away remembering the stories the kids told. They said Old Coot spied on people through that dusty window. I held my breath, and inched along her pathway.

I was about to toss the package on her back step, when the door flew open. I stood frozen to one side as I watched Miss Cogshell, in a massive, flowered house-coat, burst through to the yard.

“Oh my, I’ve lost it.” Her eyes darted about at the distant pine trees. Her cobwebby hair, whiter than spray off the crest of a wave, was swept back in a loose bun, and I watched her glasses slip down her bulbous nose. Then she saw me standing there with my mouth open. I was surprised to see a slight flush spread over her large, pale features as she pushed her glasses back up. Never being this close to her before, I was mesmerized by her size.

“I just saw my first spring robin go by the kitchen window,” explained Miss Cogshell, in an unexpectedly high, joyful voice. “Sometimes they perch over there on the clothesline.”

I glanced at the empty clothesline, and then forced myself to push the mail towards the old woman.

“Oh, my letters. Just let me wash this flour off my hands.” She gripped the handrail for support, fumbled with the latch, and then turned her bulky frame back towards me. “Do come in.”

Still holding the envelopes, I wanted to say no, but my mouth was too dry. As she opened the door, a sweet smell escaped from within.

“I haven’t baked in months. I bake today and here you are—a visitor.” Miss Cogshell continued to hold the door, her stretched-out arm like a loaf of freshly risen bread dough. Before I could come to my senses, I stepped inside.

“Now you look familiar. Which one are you?”

“Amy Henderson,” I whispered. Miss Cogshell hunched over, peered right into my face, and read my lips through her thick glasses. She looked enormous in her tiny kitchen. And I have to admit I suddenly felt like a shrimp.

“Ah, yes, you’re in that lovely home on the hill. Your father’s done well for himself.” Miss Cogshell hauled her massive bulk to the sink, turned on the faucet, and spoke softly, almost as if she’d forgotten I was there. “If only Rosie was here to see. She was always so proud of her boy.” Miss Cogshell continued to reminisce while she washed her swollen hands. “There are so many new people from away now. Especially the summer people. Every year someone seems to be coming or going. And busy! My goodness, aren’t people busy nowadays?” She stopped and looked at me, her face flushing again. “My land, how I do run on.”

I wondered how Miss Cogshell kept track of so much, until I remembered the widow’s walk and a chill raced through me. I didn’t know what else to do, so again I thrust the bundle of mail towards her.

“Oh, yes, my mail. I do thank you.” She wiped her hands dry on a clean dishtowel. Then her face saddened as she took the envelopes. “I have been so self-involved the last few weeks it must’ve slipped my mind.” She glanced through the pile while I edged back towards the door. “Looks like someone cares about this old coot after all.”

Did she say old coot? My jaw must have dropped a mile, but Miss

Cogshell was too busy ripping into her letter from France to notice. She grinned at the rainbow stationery and then put it back on top of the bundle.

“I’ll leave these until later. Right now I’ve got to get you some cookies to bring home to your family.” She reached over a row of cookbooks, got down a flowered china plate and gently stacked it with hot gingersnaps.

I fidgeted with my zipper pull while I waited, suddenly needing to go to the bathroom, yet too afraid to ask. My eyes wandered around the cluttered kitchen. A heap of newspapers was stacked next to a curio cabinet, and countertops were layered with odds and ends; only the stove shone spotless. An open cupboard revealed piles of packaged junk food—chips, Twinkies, Devil Dogs. Several faded calendars were tacked to the wall, and hanging in the window was half an old bleach bottle with ivy spilling out of it. Little cups with green sprouts sat in a row on the windowsill.

“Lupines,” she explained, catching my glance. “I’ll get those into the ground in the next month or so, God willin’.”

Finally, she had the plate ready. “You’ve got your Grandma Rosalie’s eyes, you know.”

“Thank you,” I murmured, as I balanced the plate on top of my mail and pushed out through the back door. That wasn’t so bad, I decided.

I had happy memories of Gram Rosalie and could still taste her blueberry pies. Nancy and I spent many mornings picking berries and then Gram would help us turn them into fancy pastry. I’d always make a special mini one in a tiny tin. Just the plumpest, bluest berries would go into my pie and every fork press along the edge of the crust would be as perfect as I could make them.

I tried to picture Gram’s eyes. I was only nine when she died but, yes, I was sure they were blue, not brown, so the old lady was evidently crazy.

With a great sigh of relief to have made my escape with all my body parts intact, I hurried for home.

Call Me Amy

Call Me Amy